A Great Idea Before its Time (and Dropbox)

In 2001, I tried to start a business based on code I had developed for Yale to enable online registration and management of yearly class reunions. Reunions are multi-million dollar events, and the system I developed in 1999-2001 was used to manage Yale's reunions for 15 years until it was replaced by a Salesforce-based system.

I used half of my AP credits to skip a semester and flesh out the idea further. I set up an office in my mom's basement and set to work writing the business plan. Ultimately, I concluded that universities were so slow moving that I would need a partner (or acquirer) for help with the sales process. My colleagues at Yale helped arrange a meeting with the company who was building their alumni network. The dot-com bust was already in full force, and then 9/11 happened. The company thanked me for my presentation but passed. I wasn't passionate about event registration, and there was already a well-funded competitor (Cvent.com) that I correctly predicted would dominate the space.

As with most startups, my initial idea wasn't great. On the bright side, I identified a problem that most people had yet to experience – synchronizing documents across multiple devices. You've heard of DropBox, right? Well, this was 2002, and DropBox was founded 5 years later.

Sure, you could use rsync to sync your files, but it was too complicated for 99.999% of people. The primary reason for DropBox's success is its simplicity. Rsync is complicated to configure, prevents people from sharing files with friends and won't let you access files on a public computer.

It gets easier with practice

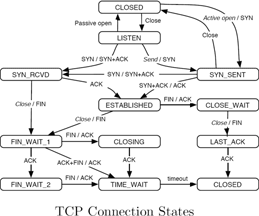

I decided to start from scratch and create a synchronization system that used the protocol that web browsers and web sites use to communicate so you could access your files with any browser on any computer. It was convenient that I was also taking a class on computer networks, so I was familiar with complex asynchronous network programming from an assignment where we implemented error-correcting TCP over lossy UDP.

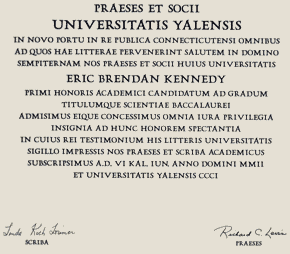

If you read the paper, it says that I was going to port the system to Windows after graduation. That was the plan — until finals week. I had finished the senior project, but had so much work to do for a project on Dutch Auction IPOs that I tried to stay awake for 36 hours. Creating graphs of the data put me over the 20 MegaByte quota (yes, that's all we CS majors received), and I was so tired that I accidentally ran rm -rf on my home directory while trying to get under quota. As the previous link explains, once you delete something in Unix, it can only be recovered from a backup, unlike on a PC. I had been working from 10am to 5am every single day that semester to fit in an extra 2 CS classes (4 CS total + a history class) so I could graduate with a B.S. in Computer Science instead of a B.A. At the end of the semester when the Alumni association also needed new reporting features for the upcoming reunions, even those crazy hours weren't enough.

Freaked out, I went to Stan Eisenstat, the head of the department and all-around Unix guru, and begged him to restore my work from the server's backups. Stan had a longstanding policy of reducing the grade for an assignment by 10% for every day that it was late, and since the deadline for the senior project had arrived, he probably thought I shouldn't get credit for fixing any bugs after the deadline. He only restored the executable and postscript paper for my senior project even though it would have been trivial for him to restore an archive of my entire directory instead. I was so exhausted and relieved to get back a working program (so I could graduate!) and finished paper that I didn't argue with him to restore the source code. I just wanted to sleep.

It was a nail-biter demonstrating the program to my adviser since if anything went wrong I would be screwed. Synchronizing binary files between multiple disconnected computers over a custom-built web server and HTTP client isn't easy to get right. Thankfully, the program worked flawlessly and I got an A. I never did tell my advisor that I lost the source code and he never asked to see it. He did ask me to add an appendix to the paper, and that required some expert PostScript programming...

There's something very ironic about losing a personal backup system because you don't have a personal backup system. If anything, it underscored the value of what I was creating. I did have local SVN source control, but without a separate SVN server those .svn folders were deleted along with the source code. I had not been concerned about a hard-drive failing since my files were on a server with RAID arrays and backups. The problem was that there was a tenured professor between me and those backups.

Overloading my schedule with 2 extra CS classes to get the Bachelor of Science degree was counter-productive because I burned out on C++ programming and decided to only apply for Program Manager jobs after graduation.

Overloading my schedule with 2 extra CS classes to get the Bachelor of Science degree was counter-productive because I burned out on C++ programming and decided to only apply for Program Manager jobs after graduation.

I knew that the idea was a few years ahead of the market and that I wouldn't be successful without a dedicated co-founder. At the time, the Seattle startup community was experiencing nuclear winter and convincing my friends to start a company was a tough sell. Even three years later, the founder of Box.net realized he needed to move to the Bay Area to raise capital and launch a similar company. Programming in C++ and writing a custom web server to handle HTTP communication made sense while I had similar projects for a Computer Networks course, but it was a lot more work and less fun than the SQL modeling I did for the project on Dutch Auction IPOs that caused me to go over quota and nuke my home directory. DropBox definitely made the right choice writing most of their code in Python.

When I joined Jobster in 2004 the CEO, Jason Golderg, found my senior paper and excitedly printed it out for all of the developers to read. File synchronization isn't sexy, but it was a better idea than the ones Jobster addressed and it's ironic that Box.net and DropBox are both very successful while Jobster was a $50 million loss for its VCs.

What doesn't kill you can make you stronger, and I'm definitely not dead yet. If you deeply believe in a new product idea but people don't see the value when you first present it, work on your pitch, finding a new audience of early adopters, and improving your demonstration before giving up. In 2002, my best friend didn't understand why file synchronization was a worthwile service because he said people could just use rysnc. He now runs a tiny company that competes with Dropbox and has since told me not to listen to his advice.

Creating a new product or service is difficult and blind optimism will wear out at the worst time. Instead, read Jim Collins' book Good to Great and focus on James Stockdale's determination while trapped in a Vietnamese POW camp:

"I never lost faith in the end of the story, I never doubted not only that I would get out, but also that I would prevail in the end and turn the experience into the defining event of my life, which, in retrospect, I would not trade."

When Collins asked who didn't make it out of Vietnam, Stockdale replied:

"Oh, that’s easy, the optimists. Oh, they were the ones who said, 'We're going to be out by Christmas.' And Christmas would come, and Christmas would go. Then they'd say, 'We're going to be out by Easter.' And Easter would come, and Easter would go. And then Thanksgiving, and then it would be Christmas again. And they died of a broken heart."

Stockdale then added:

"This is a very important lesson. You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end—which you can never afford to lose—with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.”

Collins named this principle the Stockdale Paradox, and it's the attitude that entrepreneurs need for the difficult first few years of a startup. Jeff Bezos provides a more cheerful view for well-funded companies when he says he's "stubborn on vision and flexible on details." Once you commit to building a new product or service no matter what happens, you will find ways to keep the business going through the inevitable adversity.

Follow me on twitter for more insights from working at startups since 1996.

Buying products I link to on Amazon gives me credits at no cost to you. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.